Climate Insight Series

Hiding in plain sight is one of the world’s largest CO2 emitters – cement. As the critical binding ingredient in concrete, cement is the second most consumed material in the world, after water. The sector accounts for 7-8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it a larger emitter than any individual country, except China and the US.

Despite a growing focus on climate action, absolute cement emissions are higher today than in 2015, with recent declines driven by lower output (e.g. pandemic-related slowdowns) rather than efficiency gains. Decarbonising this hard-to-abate sector will require dramatic action, from deploying new technologies at scale to investing vast sums in cleaner production. In this article we explore the pathways to achieving net zero cement.

What are the issues?

Decarbonising cement is difficult due to a combination of chemical, technical, and economic factors.

1. Calcination process emissions

Cement production’s core chemical reaction inevitably generates CO2 through a material called clinker. Clinker is made by ‘calcinating’ limestone, a process whereby a solid is raised to a high temperature to remove any impurities. In this case, the impurity is CO2:

(Limestone) CaCO₃ → CaO + CO₂ (Calcium oxide aka Quicklime + Carbon Dioxide)

For every ton of clinker produced, nearly 500kg of CO2 is released1. These are often termed “process emissions”, which currently account for c. 60% of total sector emissions and are the fundamental challenge of decarbonising cement.

2. High temperature requirements

Compounding this issue is that the process requires huge amounts of heat as kilns must reach 1450°C for several hours. These heat requirements tie the process to carbon-intensive fuels, namely, coal and petroleum coke since those have been the only reliable sources capable of delivering the required thermal energy at reasonable economic cost. Roughly 30–40% of cement’s CO2 emissions come from fuel combustion to heat kilns.

There have been many improvements in kiln efficiency and most major producers have switched from inefficient wet kilns to more efficient dry kilns. Today’s best existing kilns are operating at near the thermodynamic limits of efficiency, however, breaking the chemical bonds in limestone requires 1.8 GJ/ton and so the process will always be energy intensive.

3. Market hurdles

Beyond the technical issues, economic factors make cement decarbonisation particularly challenging. Cement is fundamentally a commodity business: it’s sold in large quantities, in a highly competitive market, with very thin profit margins. This means cement producers operate under cost pressures that leave little room for transition investments when strong external incentives are absent.

Cement plants are expensive, long-lived assets (20–40+ years), and the economics of deep decarbonisation are daunting. Upgrading or retrofitting cement plants with carbon-capture equipment, new kiln systems, or novel processes is capital-intensive, often costing hundreds of millions of dollars per plant, with little immediate payoff in product volume or quality. McKinsey estimates that the cement industry will need to spend an average of $60 billion annually from 2021 to 20502 focused largely on building out low-emissions production capacity and adding Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (CCUS) to existing kilns. Simultaneously these process changes will incur production cost rises, including operating costs, capital charges, and depreciation, of up to 45%3. Cement plant owners have therefore been reluctant to write off existing facilities early or undertake expensive retrofits to younger assets that don’t affect yield or profits.

Policy and market factors further complicate matters. If a producer moves ahead with costly CO2 cutting measures, they risk losing market share to competitors who don’t incur those costs. This classic carbon leakage problem has historically disincentivised unilateral climate action in cement. However, new policies have started to correct this. Building standards have also been slow to adapt, where outdated building codes can require traditional cement compositions, which limits the market for lower-carbon alternatives.

What are the solutions?

After decades of incremental improvements, reaching deep decarbonisation in cement will require deploying multiple strategies in parallel. No single fix can solve the problem, but a combination of innovations provides a realistic pathway.

Carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS)

Because cement’s process emissions are inherent, capturing the CO2 at the source and either using it or storing it permanently underground may be the only way to eliminate those emissions at scale. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates the industry will need to capture up to 90% of process CO2 by 2050 to meet climate targets4, and the Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA) estimates that CCUS will account for 36% of remission reduction by 20505. In short, carbon capture is the pivotal long-term solution to address the inherent CO2 from calcination.

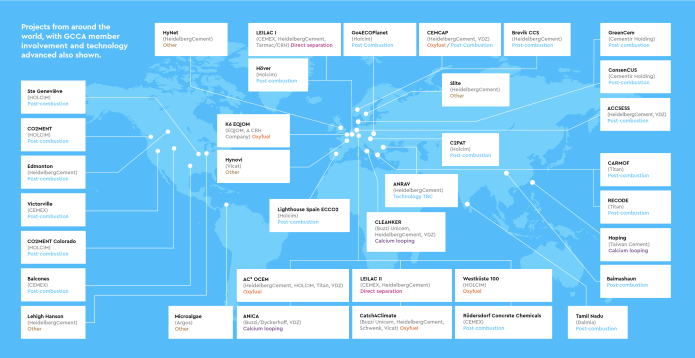

While there has been meaningful progress in CCUS technology this decade, including many projects in the demonstration phase6, the technology’s historical track record has fallen short of expectations. Progress has been slow and deployment relatively flat for years, with only one operational industrial scale cement facility with a CCS installation; Heidelberg’s Brevik Cement Plant, which has been in operation since the summer of 2025.

Projects among CCUS members

Source: https://gccassociation.org/2050-net-zero-roadmap-one-year-on/ccus-progress/

The major barrier to wider adoption of CCUS will be energy costs, with the most advanced technologies nearly doubling the cost of cement production in some estimates. Accordingly, when looking at the transition plans of the world's major cement producers, only a handful believe that CCUS will play a role in decarbonising their operations through to 20307. This is consistent with the GCCA’s roadmap for only 10 CCUS plants to be operational by 2030. Beyond 2030, the costs of CCUS systems are projected to decrease significantly driven by increased technological efficiencies in capture and increased storage capacities8. Realising the promise of CCUS depends on the commercial viability of these projects and their success in cutting operating costs.

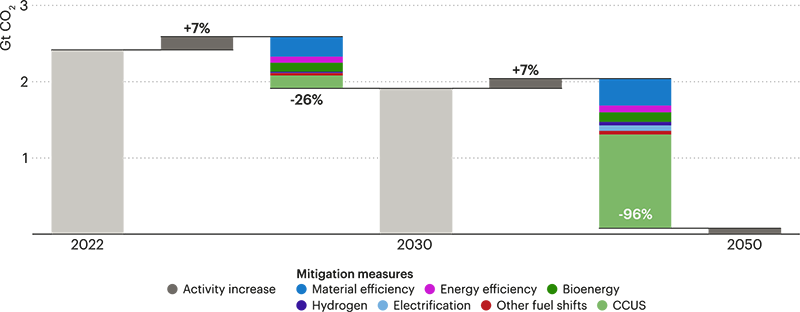

Emissions reductions by mitigation measure

Source: https://www.iea.org/reports/cement-3

Clinker substitution and novel cements

Another key decarbonisation strategy is reducing the amount of clinker needed in cement, since clinker production is the source of most emissions. It is also the area in which most cement firms and the industry associations believe significant decarbonisation can be achieved in the short to medium term.

The global standard ‘Portland cement’ is ~90-95% clinker. By substituting a portion of that clinker with other materials that have little or no process emissions, manufacturers can directly lower the CO2 per tonne of cement. Traditionally these substitutes have included fly ash (a coal power byproduct) and blast-furnace slag (from steelmaking), therefore in a decarbonising world, the supply of these Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) will be in sharp decline, and current sources fall far short of what is needed for decarbonisation.

As such, the sector is turning towards novel SCMs. Promising alternatives include calcined clay, ground limestone, and agricultural waste ashes (e.g. rice husk). Some of these alternatives have 20-30% lower carbon footprint than Portland Cement, however, due to their unique characteristics they aren’t a total substitute as they do not meet performance criteria9.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) Net Zero Scenario by 2050 estimates that reaching Net Zero will require a reduction in the clinker to cement ratio to around 0.57 per tonne down from 0.71 currently. Sufficient availability of clinker substitution materials is therefore a key driver in achieving the objective.

High clinker replacements can affect early strength gain and building codes or standards have been slow to accommodate new cement blends. Nonetheless, progress is being made – standards bodies (like ASTM and the EU) are updating codes to allow higher SCM use.

Clinker substitution is a practical way to cut emissions by using existing materials more intelligently, provided supply and standards issues are managed. Significantly, reducing clinker ratios reduces the cost base. Research by Rothschild & Co Redburn indicated that while clinker costs are approaching €135/t a tonne, popular SCMs range from $30-$60 a tonne, the relatively higher percentage of SCMs used by the larger European producers has been a key profit driver in recent years10.

Cost ($) and carbon emissions (kg) of different SCMs per tonne.

Source: Rothschild & Co Redburn, Industry sources

Fuel switching and kiln electrification

There are two broad approaches to reducing the carbon intensity associated with meeting the thermal energy requirements:

Alternative fuels: Cement kilns are relatively well suited to burn a variety of fuels due to their high temperature and long residence time. For years, especially in Europe, cement plants have been incrementally increasing the use of industrial waste, municipal solid waste, used tires, and biomass residues. These alternative fuels can be partly carbon-neutral (some wastes like plastics are fossil-derived but using them for energy replaces other fuels and avoids landfill methane). The European cement industry already sources over 53% of its energy needs from alternative low-carbon fuels11.

On a global basis, however, alternative fuels are used for only 5% of current energy requirements, far from the 86% required to reach Net Zero by 205012. There is substantial room to expand alternative fuel use13. There are side benefits too: less waste to landfill and reduced fuel costs in some cases (companies often get paid or obtain waste cheaply). The challenges include ensuring a consistent feedstock quality and supply is constrained within emerging markets. Community perceptions are also a challenge; burning waste can raise local pollution concerns, so it must be done with proper emissions controls.

Electrification of kilns - The most radical transition approach is to use electric power as the heat source for clinker production, instead of combustion. This can be done by electric resistive heating (essentially, heating elements or induction heating around the kiln) or plasma torches powered by electricity. These techniques are still experimental, and no full-scale electric cement kiln exists yet, but an electric cement kiln powered by renewables, coupled with CCUS could provide near zero emissions cement.

Scaling from pilot to a million ton/year cement plant is a huge leap, however the allure and promise of the technology makes it an attractive option for producers to explore. Electrification as a means of decarbonisation is contingent on the supply of renewable energy. If the electricity isn’t produced by renewables, no significant real-world emissions reductions are achieved, and the emissions simply migrate from scope 1 to scope 214. The WEF estimates that by 2050, the cement sector will need about 624 GW of clean power generation capacity to electrify processes in a net zero scenario, it will also only be scalable where low-cost electricity is abundant. While the electrification timeline is likely to extend into the longer-term, with wider deployment expected from 2040 onward, it provides a vision of truly zero-carbon cement production.

Policy and market support

Decarbonising cement at scale requires strong policy frameworks and market incentives to overcome economic barriers. Key mechanisms include:

Carbon Pricing and CBAM: Carbon pricing, such as the EU Emissions Trading System, internalises the cost of emissions. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), has effectively extended this to imports, ensuring foreign producers face similar costs when exporting into the EU. This levels the playing field and encourages global decarbonisation. It will also greatly push producers towards reducing the carbon intensity of cement and accelerate the use of SCMs as the carbon cost of clinker grows exponentially in the EU as illustrated in the graph below.

Carbon cost (€/t of clinker)

Standards and procurement: Updating building codes to allow low-clinker and novel cements is essential. Performance based standards are replacing prescriptive ones, enabling broader use of alternative materials. Public procurement policies, like the Buy Clean initiative in the U.S., are also creating demand for low-carbon cement by prioritising it in infrastructure projects.

Together, these tools alongside accelerated industrial innovation are shifting the economics of cement, making low-carbon solutions more viable and competitive.

Conclusion

The world will not stop relying on cement as its primary building material where we have been using cement as we know it today since 1845. And the sector’s emissions are simply too large to ignore in any credible climate strategy.

Cement’s journey to net zero will be tough, but a clear pathway is emerging. The remainder of the 2020s will likely be focused on introducing new technologies and establishing the proof of concept. Continuing to make progress on efficiency gains, and clinker and fossil fuel substitutions are measures that could cut emissions by a third by mid-century.

Efforts post 2030 will be critical in delivering those next-gen technologies, especially carbon capture and hydrogen and electric powered kilns which will only be able to deliver the remaining emission cuts if they are scaled up and adopted at an industrial level.

By 2050, “green cement” will look very different: clusters of plants linked to CO2 storage pipelines, kilns powered by clean electricity, hydrogen and organic waste, using lower clinker ratios, and cements tailored to local materials and specific applications. The economics of the cement sector too are likely to be very different in 2050. OpEx will likely be far higher – although efficiency gains from optimised design will offset some of this. Policy drivers will also internalise carbon costs for producers. It may be the case that as these costs are passed through, cement will lose its “bulk commodity” status, making way for differentiated, low-carbon products that command a premium. Producers able to blend multiple abatement levers stand to secure early premium pools and reduce compliance liabilities.

Cement may be a hard-to-abate sector, but it is not impossible. The combination of innovation, investment, and policy support provides a credible framework for cutting cement’s emissions to net zero by 2050. The urgency of climate change leaves no alternative. The foundations of our future will continue to be built on cement - we must ensure that those foundations are greener.

Sources

1 44% of the molar mass of Limestone is carbon dioxide

4 https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Net_Zero_Tracker_2023_CEMENT.pdf

5 https://gccassociation.org/2050-net-zero-roadmap-one-year-on/ccus-progress/

6 For an overview of carbon capture projects in the cement industry

7 See Heidelerberg, Cemex, and Holcim transition plans

9 https://www.cementeurope.eu/our-net-zero-roadmap/

10 Rothschild & Co Redburn, Cement: Resurgence, Jan 2026.

11 https://www.cementeurope.eu/our-net-zero-roadmap/

12 https://www.iea.org/reports/cement-3#dashboard

13 materials like sorted non-recyclable plastics, textile scraps, sewage sludge, used solvents, and agricultural biomass can often be used in kilns.

14 Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions Greenhouse gas emissions are categorised into three groups or ‘Scopes’. Scope 1 covers direct emissions, e.g. use of natural gas, company car vehicle emissions. Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity, steam and heating. Scope 3 includes 15 other categories of indirect emissions in a company’s value chain, e.g. business travel and investments